Meet Dr. Chris Hyland, a History instructor at Alexander College. Dr. Hyland has over two decades of education experience and has published multiple articles on Canadian history.

*The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

*The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q. Tell me a little about yourself.

I am a professor of Canadian history here at Alexander College, but more than that, I think I’m an educator. I’ve been in the education business for the last 20+ years in a variety of institutions.

I started out as a high school teacher. I’ve taught high school in Abbotsford and Langley. I went overseas and spent 10 years in South Korea teaching English as a second language, so I have an ESL background.

For the last 6 or 7 years I’ve been here teaching high university transfer credit as well as university credit courses, not just here at Alexander College, but at other institutions like the University of Fraser Valley (UFV) as well as Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU).

I’ve been in classrooms for a long, long time, and that’s a big part of who I am and what I like to do, but when I’m not teaching, I really enjoy running, lifting weights, that kind of thing. The physical is always a nice counterpoint to the academic work because you sit and just think.

I am also a huge fan of Anime and Japanese culture. A legacy of living overseas for so long.

Q. What are some of your achievements and publications?

In terms of publications, my area of expertise is Canadian military history, Canada in the First World War in particular. One piece I published was on the Canadian Corps occupation of the Rhineland, which is a military history piece.

Another piece that I did is more of a war on society type thing where I looked at the University of Alberta and how the university itself was affected by the First World War — the loss of students, faculty, changes in student cultures, that kind of thing.

In my research in particular, I really like to look at the intersection between universities, military, and Canadian professoriate and Canadian society, like how do universities function during times of war?

I could make a good case that university professors were running the country during the Second World War. That’s what I research and enjoy looking at.

In terms of awards, the big one is the SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) Doctoral Award. I also received the Instructor Appreciation Award during the last Convocation Ceremony.

Q. Which of your publications or projects are you most proud of and why does it stand out to you?

I think the one that I’m most proud of is a piece that I published in the International Journal of Canadian Studies. This was all about professorial secondments to the federal government.

It’s basically a transfer of university professors to the federal government during the Second World War, and it was really interesting to see that particular process, why that happened.

Basically, the impact of Canadian professors on the Department of External Affairs, the Department of Finance, so much of the heavy lifting during the Second World War in terms of government and policy was done by university professors.

Nobody knew about that, talked about that, or understood that, and it just continues to destroy that narrative surrounding the ivory tower, you know, that somehow universities are aloof or separate from a Canadian state.

Rather, Canadian universities are integral to the fabric of what Canada is doing and have stepped up big, especially during times of war, so I think that was my best piece that I’ve done so far.

— Steve [Vice-President, Academic] mentioned you have written about Indigenization as well.

Yeah, that’s one of the big things going on here at Alexander College, and I think one of the most important things that we’re doing here.

As you know, this idea of truth and reconciliation and coming to grips with our histories and the legacies of residential schools, with Indigenous communities, and Indigenous Peoples of Canada.

Understanding those histories, understanding how Indigenous Peoples work or fit into Canadian society, or not as they choose. That Indigenization, I think, is some of the most critical and important work that is ongoing.

One of the good things about working at multiple institutions is I get to see what other people are doing on different topics, and of course in Indigenization is one of them. We have got a lot of work to do here.

I sit on the Truth and Reconciliation committee with Sebastian Huebel and others, and we’ve done a lot of really important work. We put together resources and we put together an instructor’s guide to help people get started.

I’ve also given a lecture to the college, to anyone who wanted to go, on the history of residential schools.

As I said, there’s still a lot more work to do in the sense that we have to reach out to the local communities, indigenous communities, and start working, collaborating, partnering with them to see what’s going on.

We’re just touching the edges of it now in terms of Denise Douglas, who is Stó:lō First Nation. That’s the beginnings there, but as I say, there’s so much work to be done, so hopefully we can continue some of that.

— Do you have any plans for future Indigenization projects?

Not at the moment, no. We took a break this semester, but next semester we’re going to fire up again and see where we go.

I think more than anything else it’s raising consciousness. It’s just talking to people, in the staff room or at the photocopier. It’s that conversation: What do you think about this? How can we do this?

We actually ran a survey and it was interesting because a lot of the staff for one reason or another, either doesn’t know about the history of residential schools — they recently arrived in Canada — or didn’t study it in high school or university since they’re of that age before it became really a thing and so the faculty here is rather new to this whole sort of Indigenization idea.

So you have to start at the beginning and just talk for sure.

Q. What do you like about Alexander College?

The people here are amazing. I smile a lot when I come to work. It’s an honest answer because there’s just cool people here, you know, people who are fun to work with, people who are interesting, collaborative, and collegial. Really, really, good people.

Q. What is your approach when it comes to teaching?

When I step into a given classroom, I like to find out where the students are. I find that out through conversations, you work with them in class, you see how they react to lecture material, and you see how they react to certain assignments.

My goal as an instructor, as an educator, is to take a student wherever he or she is and move them forward in some meaningful way, whether that’s from 0 to 10, from 10 to 20, or 15 to 35. It depends on the given student and it depends on the given class.

They’re all different and I think an important part of education is meeting students where they are at that particular time, in that particular space, understanding who they are, and helping them with what they need and what they want at that particular time.

You can’t do an individualized class or individual instruction for every student, but as best you can, you try to make things make sense. To help them progress a little bit further, a little bit forward, is always good.

I think one of the other things, and this is kind of unique to Alexander College, is for the international students — I’m really trying to help them understand Canada and Canadians. Who we are as a people, who we are as a country, what does it mean to be part of Canada for a little while, and why is that important?

We have a lot of those kinds of conversations, and I think that’s important, especially at an international school.

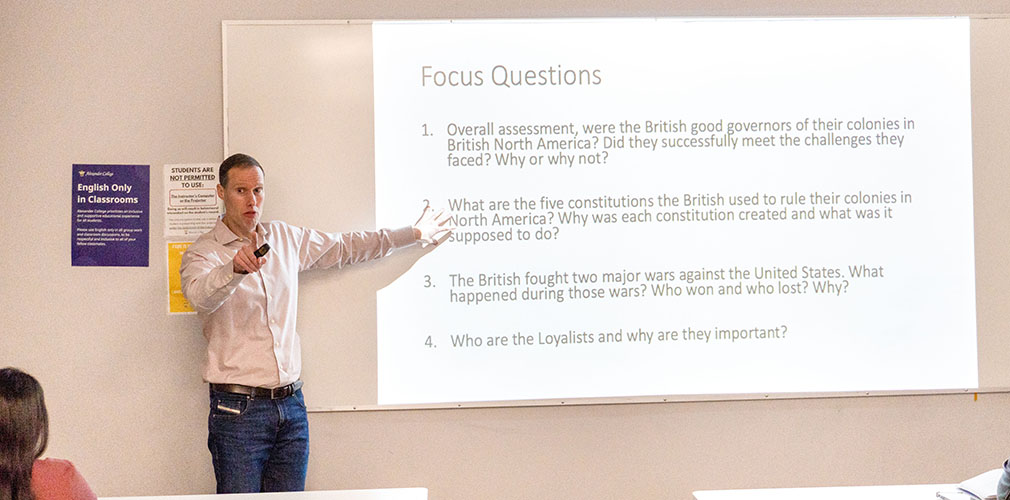

Q. What can students expect in your class?

A lot of reading.

Outside of the reading and writing part of it, stories. I tell a lot of stories and I think that’s the essence of history, storytelling and conveying these particular stories about fascinating people and events and communicating those to students in a fun and interesting way.

The idea of narrative, the idea of story, the idea of characters, these are things that students can understand and it makes history a little more meaningful, intelligible to them.

One of the main things that I try to do with history is make it relevant, make it understandable, make it intelligible. Are there pop culture references that I can bring in? Are there connections to their daily lives that I can make?

It’s like, why should I care about history? What does this mean for me? Why is this important?

Well, let’s think about this for a second. That land that you’re walking on over there actually doesn’t belong to Canada. Let’s talk about that for a minute. And you have that kind of conversation.

Q. If you had to elevator pitch history as a subject, how would you do it?

History: great stories, critical thinking, lots of fun.

Q. Do you think it’s important for students to learn history? Why or why not?

Yeah, it is. Why study history? Number one, creates understanding, understanding of different peoples, different cultures. It connects past and present.

In other words, it answers the question, how did we get here to this place at this particular time? It has great stories, it prepares people for citizenship and a way into a given society, you know, PR cards and then citizenship later on.

You can think about job training. Some of the most important skills that employers are looking for are in humanities courses, history in particular.

Whether it’s teamwork, presentation skills, public speaking, critical thinking, the ability to write and write argumentatively, those kinds of skills are transferable and in demand.

Q. What is a TV show you would recommend?

I think one of the best miniseries is probably Band of Brothers. It’s largely about a unit during the war and how they train together, work together, work through the war together and the trials and tribulations of going through that; it’s the small group aspect to war.

Often these movies and things are sort of the big scene, big picture, grand movement, but this is the narrow focus that makes it really interesting to see how it works.

Q. Are there any additional things you want readers to know about you or just life in general?

“To thine own self be true.”

Let’s see, to quote Hamlet, Polonius says to his son Laertes, “to thine own self be true.”

I think that’s really, really, good advice in the sense that you have to be who you are. Students can smell a fake a mile away. As a teacher, as an instructor, or just as a person, you have to be true to your own personality and who you are, and that’s who you should be in the classroom.

I think that it’s really important just to be honest with yourself and where you’re going and what you’re doing, and your own interests. I think students can handle that, and that would be a good thing, to thine own self be true.

Alexander College acknowledges that the land on which we usually gather is the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. We are grateful to have the opportunity to work in this territory.

Alexander College acknowledges that the land on which we usually gather is the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. We are grateful to have the opportunity to work in this territory.